For the original in Portuguese by Luã Marinatto e Rafael Soares, published in EXTRA, click here.

Rio’s Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) public housing is designed to house the poorest families—known as Band 1 financing—but are also targets for criminal group activity. After three months of investigation, EXTRA reveals that across the 64 housing complexes already built by the federal program in Rio, their 18,834 families are subjected to forced evictions, residents’ meetings led by criminals, apartments used as points-of-sale for drugs, drug traffickers interfering in who gets new apartments, beatings and murders.

To reach this conclusion, EXTRA gathered perspectives from more than 200 people, including residents, building managers, Civil and Military Police, public prosecutors, public and private workers, researchers and authorities. Furthermore, documents from the Civil Police; the prosecutor’s office, the Municipal Secretariat for Housing, the Disque-Denúncia crisis hotline, the Caixa Econômica Federal and the Ministry of Cities were analyzed. Some files were obtained via the freedom of information law. The material inspired a series of reports called Minha Casa Minha Sina (My Home My Fate), the first of which was published at the end of March.

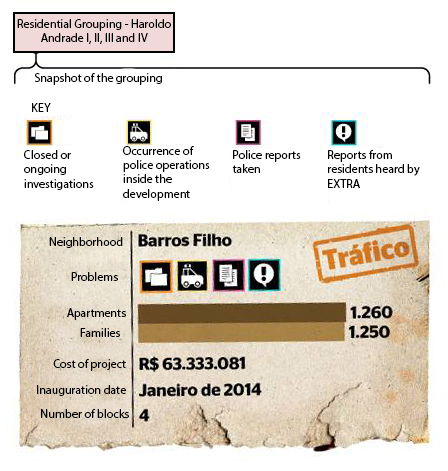

In the first report of the series, EXTRA revealed that at least 80 families were evicted from the Haroldo de Andrade I, in Barros Filho in the North Zone, following an order from the most wanted criminal in Rio, Celso Pinheiro Pimenta, known as ‘Playboy.’ A police investigation showed that the chief drug trafficker of Complexo da Pedreira, Costa Barros—a neighborhood next to the housing projects—distributed the apartments, which needy families were forced to leave, among his allies.

Last October, in the midst of a dispute between drug factions over territory in the North Zone, Playboy recorded an audio message addressed to his rivals. In the dialogue, he states that he gave houses to men who changed allegiances and joined his gang: “[They] are here, in honor, they were awarded houses, they were awarded all kinds of stuff.”

The almost 80 evicted families were not chosen at random. They were all from areas of of Manguinhos, a favela dominated by a rival faction. Shopkeeper Maria, 54 years old, remembers that night very well, in April last year, when she was forced to leave her newly decorated apartment with her four children.

“The armed criminals asked where we had come from. When they saw my contract with my old address in Manguinhos, they gave me a day to leave,” recalls Maria.

Government Responses

The State Secretary of Security, José Mariano Beltrame, learned of the invasion of the condominium through a letter from the Federal Police, which communicated the presence of “armed people preventing residents’ access.” The document was referred to the 39th precinct, where an inquiry was opened at the beginning of March to investigate the case. However, the State Security Secretariat said that only the Civil Police would make statements on the case.

The civil police confirmed there were open inquiries about the presence of drug traffic “in some developments of Minha Casa, Minha Vida,” adding that “the investigations are ongoing and are undercover.”

Invited to comment on the situation of the 80 families forcibly evicted by the traffickers, the Ministry of Cities representatives could not comment because it is a “case of public security.” Caixa Econômica Federal, which funds the project, has stated that “complaints related to possible invasions and evictions of residents are passed onto the Ministry of Justice.”

Below are the responses in full.

Civil Police:

“There are ongoing operations to expel drug trafficking from various developments of the Minha Casa Minha Vida program. The investigations are ongoing and are undercover. All complaints of crimes in these areas passed on to the civil police are checked and investigated.

“Last year, the Defrauding Office (DDEF) initiated an enquiry into fraud in the program. The report was sent to the Ministry of Justice, with arrest warrants for Diego Lazaro Mendes Moura, Bruno de Albuquerque Povoreli Ferreira, Maria da Paz de Sousa da Silva and Lupercio Barbosa da Silva.

“During one operation related to these investigations, the 31st precinct (Ricardo de Albuquerque) arrested Carlos Henrique de Oliveira, president of the Gogó da Ema Residents’ Association, in November last year due to his involvement in the invasion of the Minha Casa Minha Vida condominium in Guadalupe. According to investigations, Carlos Henrique and Paulo Aquino, who was also a candidate for state representative, acted as organizers of the invasion and so the Ministry of Justice also released arrest warrants for them. According to the Defrauding Office, Carlos Henrique is also being investigated for selling apartments in the condominium.”

Caixa Econômica Federal:

“Caixa Econômica Federal (CEF) states that, in compliance with the inter-ministerial agreement, reports related to possible invasions or forced evictions of residents in the ‘Minha Casa Minha Vida’ developments are passed onto the Ministry of Justice.

“After a reintegration process, the housing units are inspected to identify possible damage, renovated by construction workers and then given to listed recipients in accordance with the rules of the program.

“The bank also makes clear that any complaints related to possible safety issues received by CAIXA are transferred to SENASP, in accordance with the inter-ministerial agreement. CAIXA does not disclose the content of reports it has received, due to the confidentiality of information that involves security threats.”

Responsibilities

Ultimately, it is the Ministry of Cities that is responsible for Minha Casa Minha Vida. It is the body that sets guidelines, establishes rules and controls the distribution of resources between states.

Two public banks control the financial operations, Banco do Brasil and Caixa Econômica Federal, which also provide a complaints hotline for reporting any irregularities in the program to be passed on to the Ministry of Justice.

The Ministry of Justice coordinates an inter-ministerial group, set up in April last year, aimed to combat problems in the program. Meetings also include the Ministry of Cities, and the Federal, State and municipal police.

The Federal Oolice only respond to investigations of fraud in the program. Cases of common crimes, in general, are the responsibility of the state police.

The State Security Agency (SESEG) is subordinate to the Military Police, responsible for superficial policing, and the civil police, who do the investigative work. SESEG is therefore responsible for any problems related to public security in the state.

As it stands, the city and state governments, through their respective housing departments, register applying families and then coordinate the distribution of apartments depending on the project. In the first few months after the development launched, the agencies need to monitor residents through the presence of social workers, who can receive complaints about any eventual irregularities.

*All names are fictitious.